PARADISE LOST AND FOUND: A CAUTIONARY TALE

Having spent the majority of my formative years growing up in an isolated fishing village in the Gulf of Thailand, I’ve noticed a worrying trajectory in Bali, one I’ve witnessed before.

Situated right at the epicentre of southeast Asia and with something for everyone, Bali has become synonymous with partiers, surfers, culture vultures and retreaters alike, evolving into the perfect vacation spot for most demographics, a tropical mecca that has attracted people for decades.

With borders happily open and restrictions officially eased, we’ve seen hoards flock back to the island, scarpering to make up for those two years left indoors. Unsurprisingly, having been left untouched for the last 24 months, the region is struggling to suddenly operate at full capacity; with skeleton staff and half the number of businesses open left to bear the brunt of the swarms. Foreign tourist arrivals jumped 364.31% year on year between October 2021 and October 2022, boosted by further easing of Covid-19 restrictions seen in the spring of 2022, the velocity at which the island has had to snap into shape so-to-speak, has been unprecedented.

Consequently, infrastructure is reaching a vivid breaking point.

Roads are currently grid-locked in bumper-to-bumper traffic, accommodation is almost impossible to come by – and if by some miracle you do find it, it’ll cost you a small well-earned fortune – and find a top tier restaurant you want to dine at? Be prepared to book ahead a few weeks or queue for 30 minutes.

Bali has swiftly morphed into the most exclusive club in southeast Asia; one which you’ll struggle to enjoy without a country worth of connections and someone nonchalant about their income bankrolling you.

One of the vastest issues affecting the island has been the unparalleled jump in property prices for both rental, and purchase in Bali hotspots. With this, extreme stories of rent doubling, or even tripling on the price they were pre-pandemic are becoming normalised; a likely consequence of the large number of wealthy individuals that chose to relocate to Bali during the pandemic due to its loose enforcement of restrictions. With this, a higher economic precedent was set, pricing a lot of the people who’d lived here out of the very neighbourhoods they’d found a home in.

And property isn’t the only thing that has become increasingly expensive in Bali. Ten years ago, grabbing a Bintang at a bar would set you back only 25k (£1.30), nowadays, it’ll cost you approximately 75k (£3.90), not a far stretch for what you’d pay in Europe or other more economically developed countries.

The rising costs in the region, coupled with the endless construction and subsequent waste issues and pollution, doesn’t scream ‘island paradise’ like it used to. And just a short flight away, there’s a perfect case study of what happens to a tourist economy when this type of travel reverberation is left unchecked, but then capitalised on heavily when the opportunity arises…

A NEIGHBOURING EXAMPLE

In the early 2000s, Thailand saw its own massive boom in tourism which ultimately ended up negatively shifting the public’s perception of the idyllic paradise in a similar fashion to what we are currently experiencing in Bali.

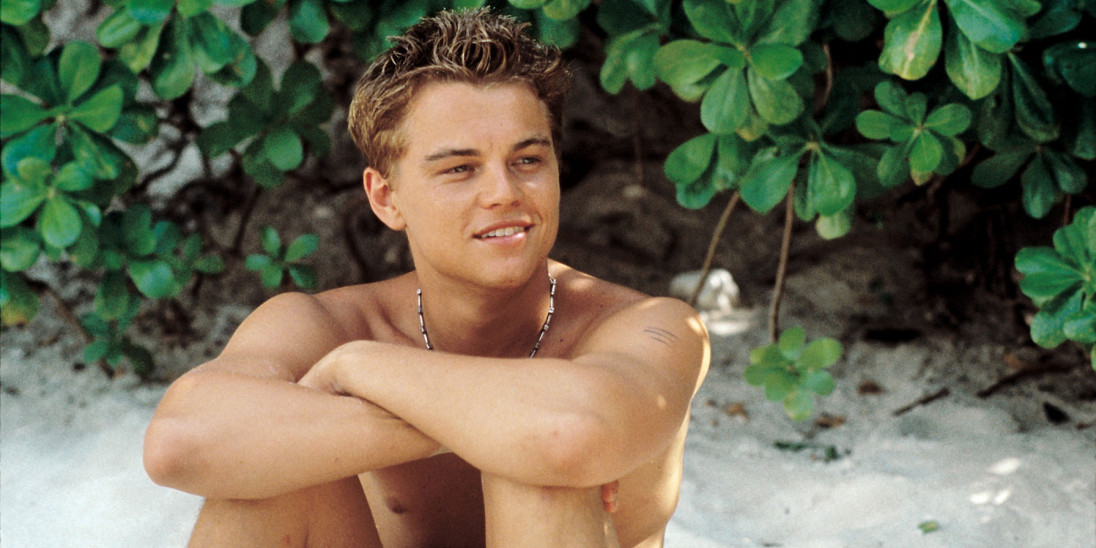

Thailand had always been a destination synonymous with beaches, coconuts, and palm trees; but coupled with the breakout success of the film (and better book) The Beach, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, the destination was catapulted onto the map as the place to go when you were young, wild, and carefree. It became the backpacking and party hotspot for the world, attracting record levels of tourists. Cornell University reported on the impact that the film had on Thailand’s tourism industry, they noted it was “probably the best and most effective advertising for Thailand’s tourism during this period.”

When you take into consideration the contemporary historic unease in neighbouring Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, Thailand reaped the benefits of its relatively peaceful governmental reputation in the late 90s and early noughties, enjoying and devouring the largest slice of the tourism cake in the sub-continent.

With this, infrastructure rapidly adapted to the revised level of tourism it was being unwillingly forced into. Huge premises were built to accommodate increased demand, fresh businesses opened, and the local economy lapped up the inflated income it was newly accruing.

And just like that, localities were completely morphed into something that didn’t slightly resemble what they once were. Ex-pats and repeat visitors who characteristically travelled with composure and respect, found the places that drew them to the country originally in a completely different state. The magic of the region was rapidly being stripped away to make room for a new type of tourist… tourists with money, little care for the culture and more intent on getting f**ked in every sense of the word.

This loss of character wasn’t only apparent in the changing landscape but reflected back in tourist numbers. The World Tourism Organization (World Bank) documented a sharp decrease of international arrivals in Thailand in the middle of 2002-2003, before numbers plateaued and then fell again between 2006-2009. And following a short-lived rise, there was once again a sharp decline of visitors during 2012-2014.

It can be argued that Thailand didn’t refer to any sustainable model when it came to their own tourist influx. Met with building sites, crowded beaches, dirty roads and not the picture-perfect Thailand they had seen DiCaprio frolicking on in The Beach, people were disappointed. Subsequently, the recurring tourism the country needed to survive, the type that provides economic sustainability, didn’t emerge in local communities as it should have.

Consequently, when the eventual plateau of holidaymakers came, an eerie scene of empty hotels, quiet restaurants, and an atmosphere of ‘what could have been’ descended on the idyllic hotspots within the country.

There is no denying that booming tourist economies provide undebatable and undeniable positives when it comes to opportunity and income. However, we’ve repeatedly witnessed how important it is that this type of growth is sustainable, predictable, and reliable, for the local environment and its people to flourish.

Sounds like a familiar story, doesn’t it? A similar curve is appearing in Bali.

MEANWHILE, IN BALI

Canggu has quickly morphed from rice paddies and a couple of surf shacks into the new ‘it’ place to be – or be seen, as a consequence we’re witnessing in real time a rapid transformation, highlighting a worrying trajectory that could lead to the area entering its own crash. It’s the rate of this growth that’s concerning here, what occurred in Thailand over a period spanning a few years feels like it’s happening here in the space of a few months.

The numbers and density of guests and tourists in the Canggu area of the island has grown immeasurably during the last 12 months, therefore the gap between supply and demand has grown so far that many sectors are struggling to catch up. The danger of this type of ascension to the top of the tourist food-chain comes when you look at the long-term ramifications of such momentum.

The consequences of such popularity in the tourist sphere are ever more obvious when you look at Thailand as a case study, or blueprint.

BOUNCING BACK

The neighbouring paradise is just beginning its rise back as a choice destination, for tourists and expats alike. During the pandemic, Thailand held itself to tighter restriction, and continuously enforced said restriction. Thus, it cornered itself into the box of a less appealing option for vacationers.

Right now, we’re seeing a shift in the opposite direction. Those tight restrictions which relegated Thailand as a tougher holiday option, are the exact reason both expats and tourists are making their way back to the country, respectively either relocating, or choosing it for their next getaway.

Thailand’s unique approach to reducing the long-term impacts of mass tourism were strong yet undeniably effective in rewinding the ill effects the industry had on the country. Most notably the government closed Maya Bay, the beach where DiCaprio captured the stunning natural beauty of the Phi Phi islands. The closure which aimed to restore the damaged eco-systems of the area, left the location off-limits for four years to tourists. In 2022 the bay temporarily opened to visitors, before closing after the summer, so the ecological impacts of the few months of opening could be fully examined. At the time of writing, Maya Bay is closed.

With the benefits of such legislation now being reaped, and the new easing of laws adjacent to drug control – with marijuana use being decriminalised – Thailand has never been a more attractive destination for holiday makers. Juxtapose that with the law changes we’re seeing in Indonesia, and it’s no surprise that tourists are considering the more liberal neighbour as their next vacation destination. While Indonesia already bans adultery, the new ban on pre-marital sex and cohabitation between unmarried couples has caused an unnecessary media storm in a country that already stands behind some quite rigid freedom of speech legislation. Wether the laws are upheld in time or not, the connotations of such movements can leave Bali feeling outdated in comparison to its South East Asian neighbours, and the wider tourist economy.

With this in mind, the culture and people that make Bali so memorable need to be protected to keep enticing international arrivals to this tropical paradise, amidst the legislative changes. Quality tourists don’t travel to Bali to stay in Mediterranean styled villas, eat exclusively Western food or drink cheap beer. And whilst this segment is essential for the economy, visitors are increasingly wising up to the fact that Thailand offers this, at a cheaper and less congested bracket. The repeat tourists the island should be aiming to attract fall in love with Bali for its notable characteristics; its Hindu cultural rooting, its unique architecture, and its delicious local food, to name a few of the many things that make this place special.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

On top of bringing in legislation that would protect these sectors, more must be done to control the stark overcrowding that we’re all by-standing to right now. Among a few issues, there needs to be a call for a rehaul of the roads in Bali. There has to better island and town planning to reduce the traffic congestion on the shortcuts, and permanently prohibit cars, taxis and vans making their way down these already dangerously thin roads; thus additionally reducing motorbike congestion on Jalan Raya Canggu.

More investment needs to be funnelled into the areas that need it, a stark example would be the extremely tired region of Kuta. A regeneration in this area would ease the strain on the current hotspots of Canggu and its surrounding areas.

It’s safe to say that more control on building regulation should additionally be considered. The amount of properties being built right now is at a velocity like no other time in recent memory. Subsequent to the pace at which these buildings are going up, it’s safe to assume that the same buildings can’t have been built to the highest calibre, affecting whole streets that’ll need renovation in the not-so-distant future.

Furthermore, the lack of regulation or thought around planning permission is vivid. A street can only support a finite number of avocado on toasts throughout a 12 month period, when there are low season numbers passing through.

Generally, it’s apparent that more needs to be done to control and manage the growth spurt we’re seeing along the West coast, so no one area is drawn too thin and collapses in on itself, as we’ve seen with Kuta, and even parts of Seminyak in recent times.

There has to be a thought out symbiosis between an economy that relies on tourism, and one that protects and preserves its local environment for the longevity of its own survival. With such appealing options right on its doorstep, it might just be the time for Bali to reground itself in the aspects of it that had people visiting in the first place, before that individuality is lost with no care or respect for local traditions and culture that made the island what it is today.